Why Is The Illinois Supreme Court Race Competitive?

How can a state court map drawn by Democrats in one of America’s bluest states lean Republican?

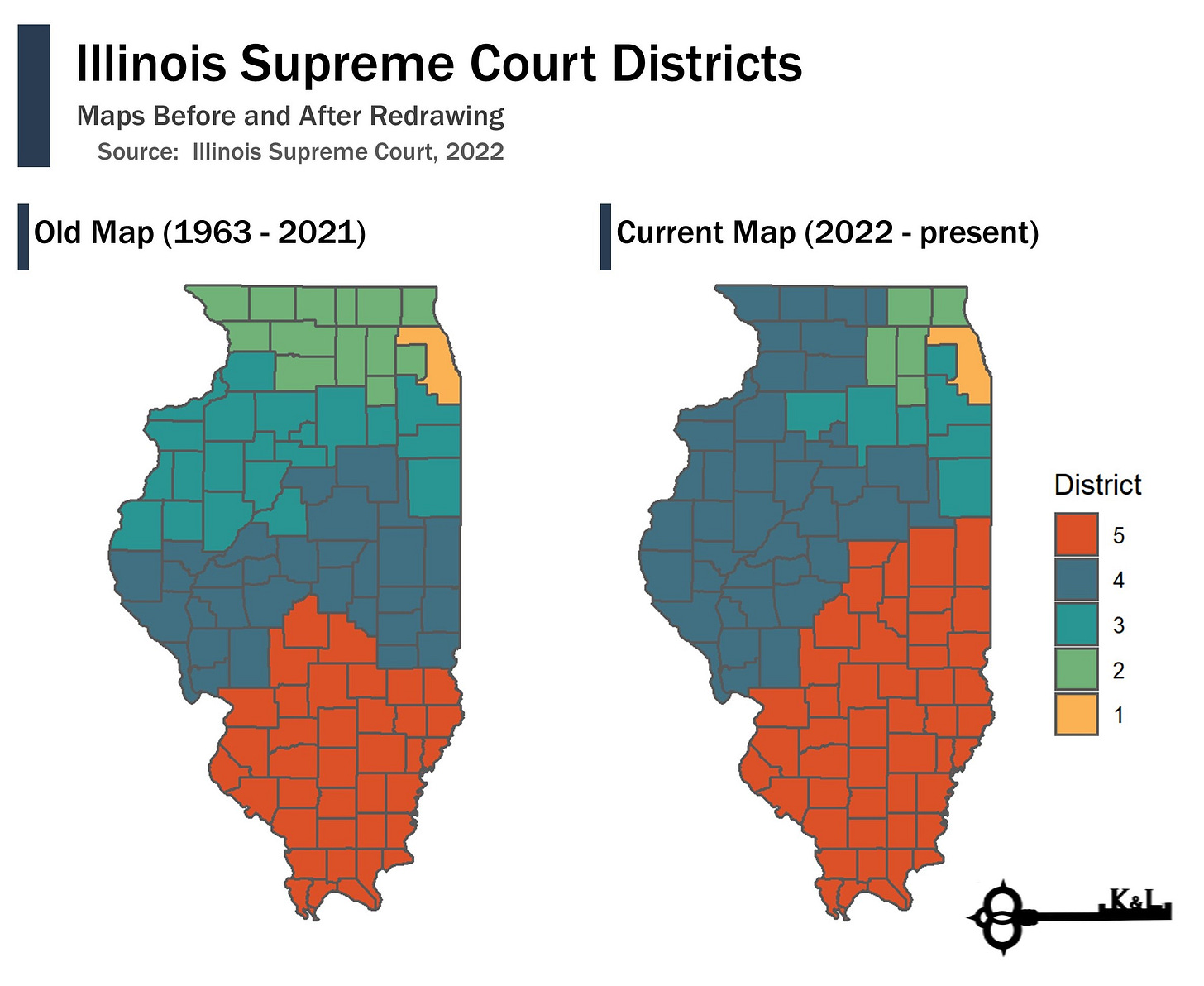

Last year, Democratic state representatives in Illinois redrew the Illinois Supreme Court district map for the first time in almost 60 years. Proponents of this new map argued that it was necessary to update districts for a state that had changed a lot since the 1960s, leaving the districts with severely unequal populations. Critics, however, attacked the process for a lack of transparency – both the new map, and even the fact that there would be a new map, were announced just a few days before the bill was voted on, leaving little time for public input. Republicans especially argued that this rush was because Democratic legislators wanted to keep control of the process for themselves, to redraw the map to their own advantage after Democratic Justice Thomas Kilbride lost his retention election in 2020 (the first time any Illinois Supreme Court justice has done so). Despite this criticism, the bill passed on party lines, and will be used for the upcoming Illinois Supreme Court elections this November.

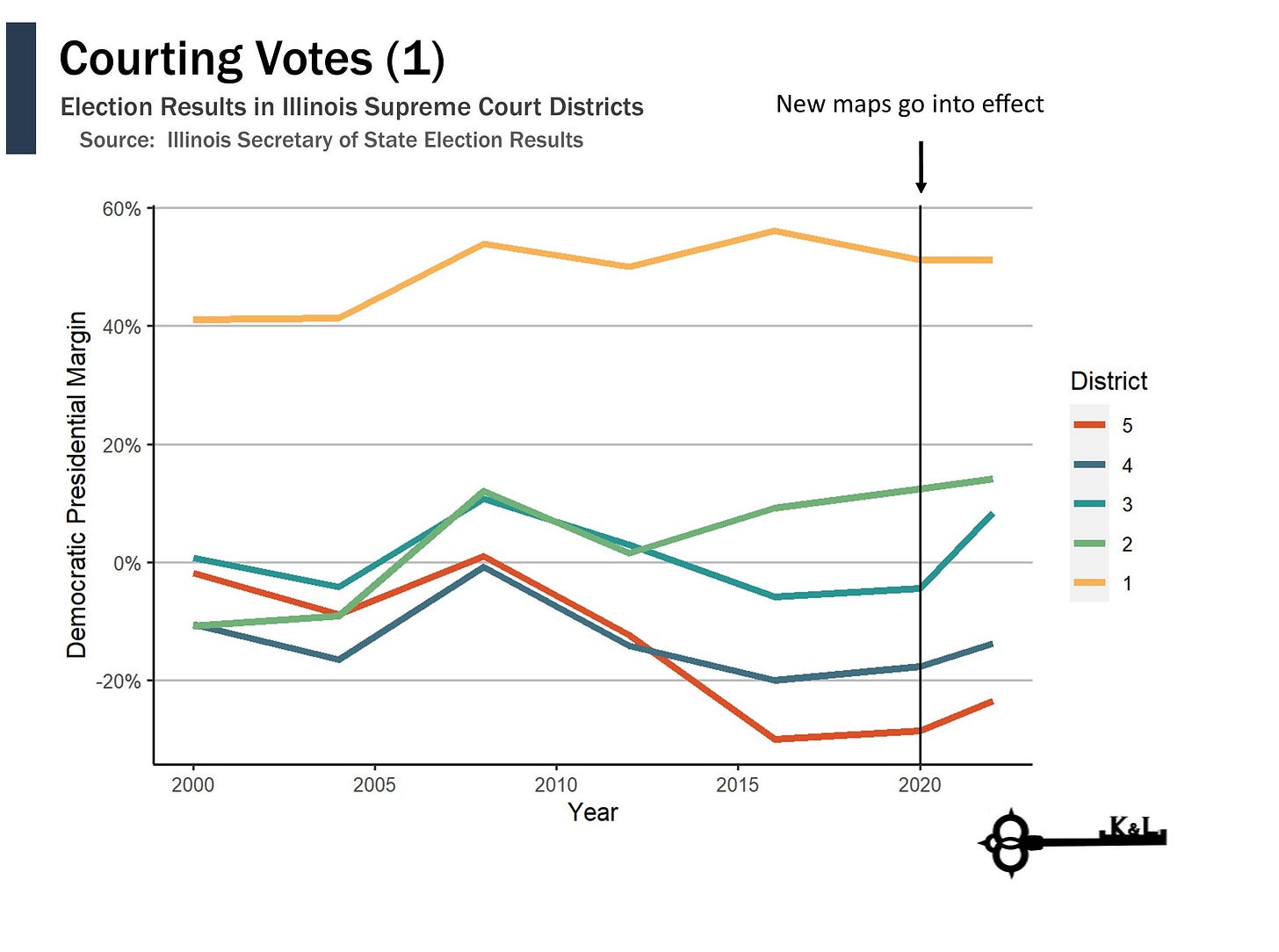

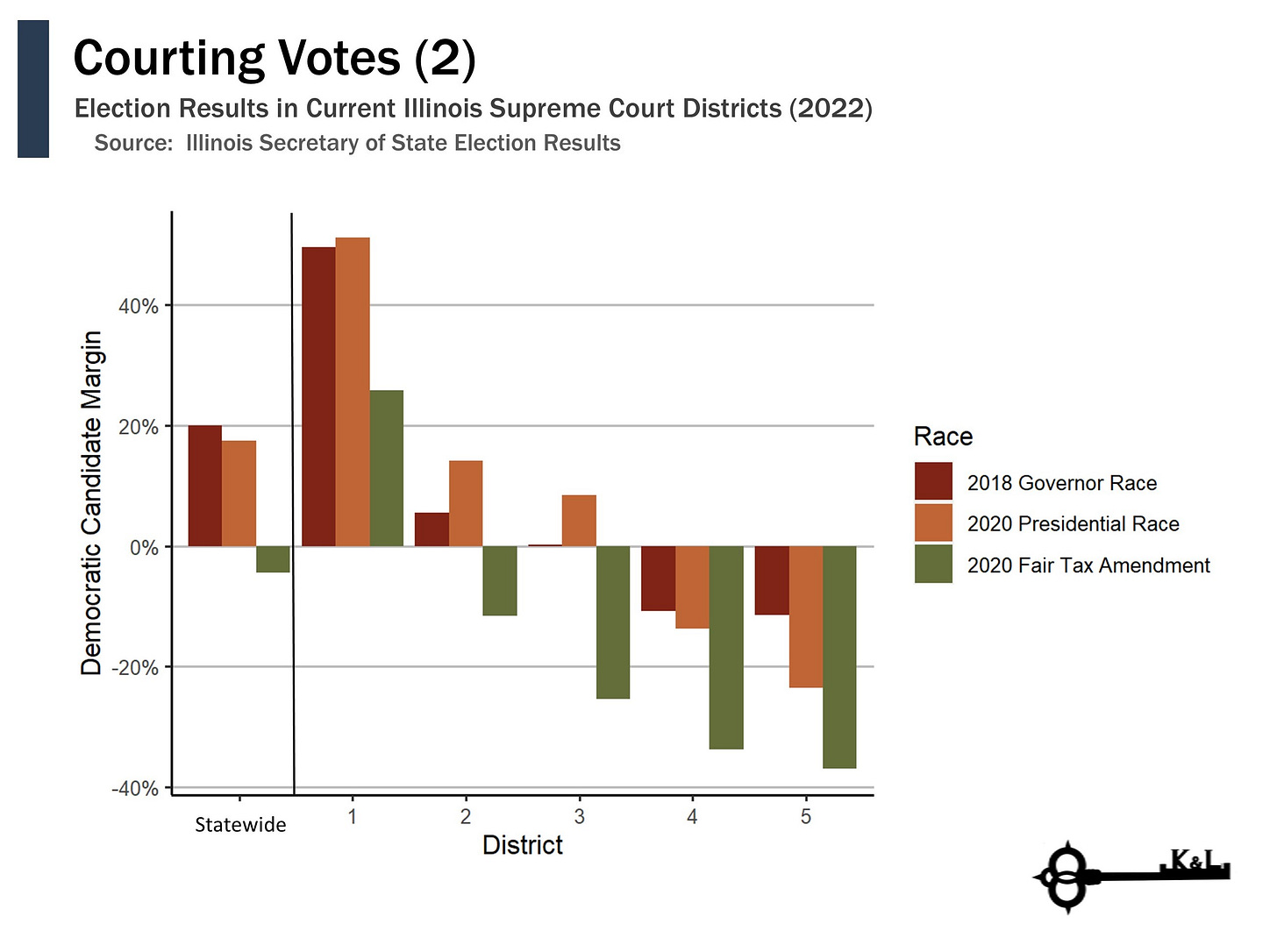

For all the accusations of Democrats drawing the map in their favor, though, the race for the Illinois Supreme Court this November is actually somewhat competitive. This is especially odd because the statewide races, such as that for Governor or Senator, are not competitive at all – the Democratic candidate is heavily favored, with polls showing that most Illinoisans intend to vote for them. This discrepancy is made even more clear when looking at past election results in detail – the current Democratic Governor, J.B. Pritzker, won the state overall by 20%, but the precincts making up the median Supreme Court district in the new map voted for Pritzker by just 5%. How is it possible that a map drawn by Democrats, in a state where most will vote for Democrats, can seem to such a degree benefit Republicans?

Having a state supreme court elected from separate, geographic districts makes it difficult to ensure equal representation. In fact, only three other states – Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi – have state supreme court justices represent districts like this. In all other states, each justice represents the state as a whole. In Illinois, though, these districts determine more than just who votes for the Supreme Court justices; they also serve as appellate court districts, so determine which appellate court a circuit court decision is appealed to. This means that redrawing districts is not just a matter of reassigning voters, but rather requires reorganizing a whole judicial bureaucracy. But while keeping one map for 60 years removes this hassle, it also means that if the state’s population changes, districts might end up with very different numbers of voters.

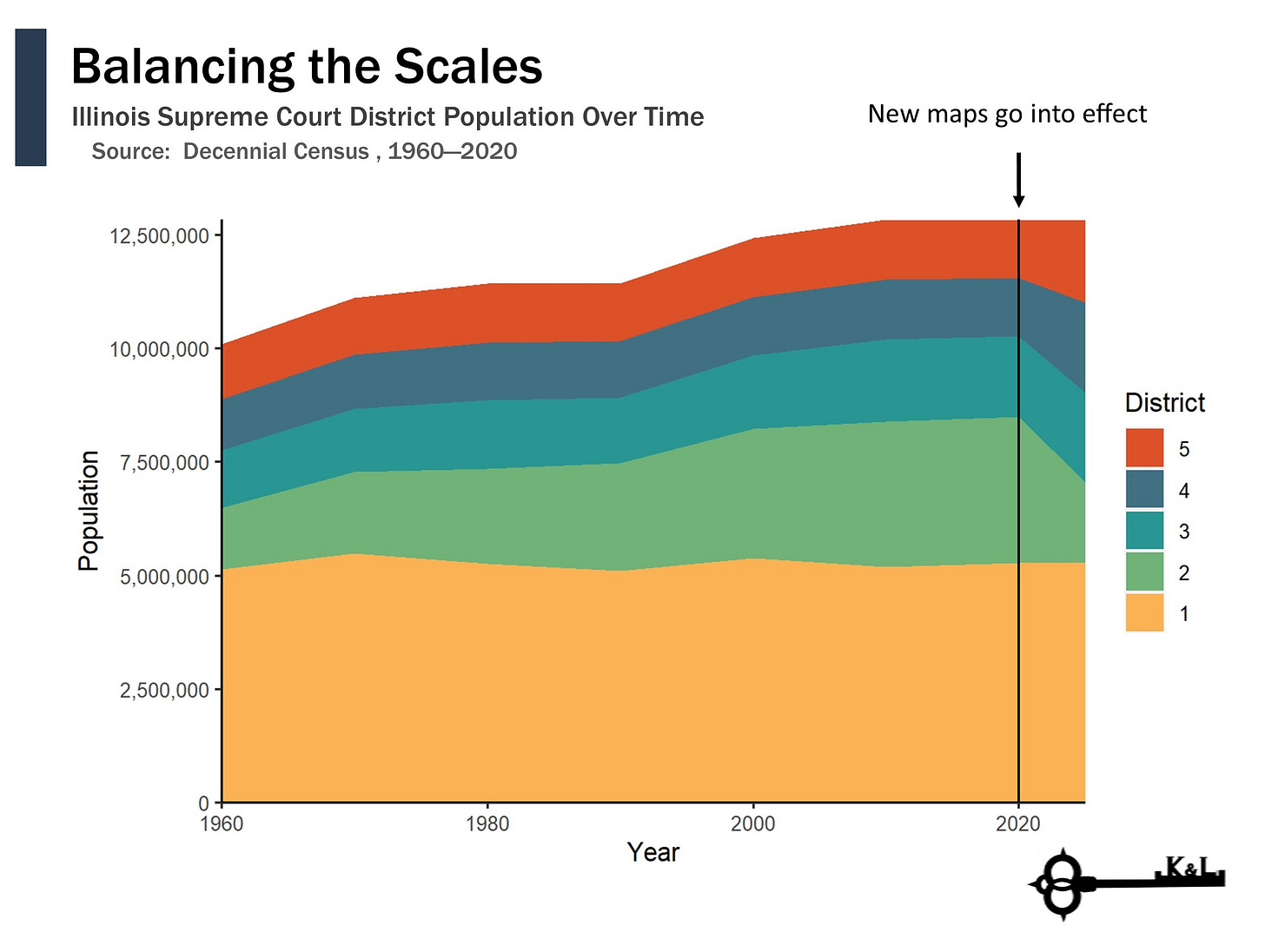

In fact, as of 2020, the 2nd District had more people than both the 4th and 5th Districts combined while still only electing one justice, with 3.2 million to their 1.3 million each. When the map was drawn back in 1963, the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th Districts all had a little more than 1 million people. The 1st District, which contains all of Cook County, had just over three times that at 5.1 million, but as a result was allowed to elect three justices instead of one, so everywhere in the state, there was roughly one justice for every 1.4 million people. Over time, though, the collar counties in Northeast Illinois grew faster, while downstate communities shrank, leading the 2nd District to get bigger and bigger, especially relative to the 4th and 5th Districts.

This led to the nominal justification for redrawing the map. Generally, democracies endorse the idea that everyone’s vote should count the same. This means that districts must have the same population, or you can end up with two equal groups of people electing different numbers of representatives, giving the votes of the group with more representatives more weight. Thanks to US Supreme Court rulings in the 1960s, state legislatures and the US House of Representatives are required to abide by this standard of “one person, one vote.” The Illinois Constitution similarly requires that the Illinois Supreme Court districts be of “substantially equal population,” but as mentioned before, does not set any specific timeline for updating them. It was this clause specifically that Democratic lawmakers cited as their justification for the new map.

To their credit, the new map did leave the districts fairly close in population, all having between 1.7 million and 2 million people. It also tilted the map to lean more towards Democratic candidates. While the 3rd District did not need to change significantly in population, the new map took the opportunity to add liberal-leaning DuPage County and remove some more conservative-leaning counties in western Illinois, resulting in more Democratic-leaning voters, and fewer Republican-leaning voters, in the District where Democratic Supreme Court Justice Kilbride had recently lost an election.

However, another quirk of Supreme Court districts meant that Democratic lawmakers could only mitigate the District’s Republican lean, not reverse it. In fact, the 2nd and 3rd District are still to the right of the state overall, in theory making it possible for Republicans to win a majority of Supreme Court seats with a minority of the vote. This is thanks to the structure of the state court system. Lower courts are organized at the county level, so since the Supreme Court districts are composed of these lower courts, they are not allowed to divide counties across different districts. This leaves lawmakers a lot less flexibility in drawing new maps that they have with, for example, state legislative districts.

For one, the requirement to keep counties whole effectively “packs” all the Democratic-leaning voters in Cook County into the 1st District, diminishing the impact of their votes. The vast majority of voters in the 1st District tend to prefer Democratic candidates, to the point that Pritzker won by 50% there in 2018, leaving little doubt which Illinois Supreme Court candidates will win there in November. However, the margins are so big that even if most voters statewide pick Democratic judicial candidates, a lot of those votes are going to 1st District candidates that already have more than enough to win, leaving the remaining districts more Republican-leaning as a result. This is the basic principle behind the gerrymandering tactic of “packing” voters of the opposing party, or minority voters, into one district where the extra votes go to waste. While it is not an intentional feature of this map, the result is the same – a Supreme Court election that leans to the right of the state overall.

For another, it also makes it difficult for Democratic legislators to “crack” Republican voters. The accompanying tactic to packing, aspiring gerrymanders can also split voters of the opposing party, or minority voters, across many different districts, so that even if the targeted group has enough votes to win one or more of those races if they were kept together, split up they are a minority in all of the districts. If they could split counties, Democratic legislators could “pack” a large number of Republicans into one district to reduce the number in the remaining three districts, and then “crack” the remaining Republican voters across those three districts so that none of them have a Republican majority. Since counties cannot be split, however, it is hard to separate Democratic and Republican voters, so packing and cracking with this precision becomes very difficult.

For all these reasons, the new map has ended up arguably more fair than the old one. Redrawing districts to have the same population means that for the first time in decades, votes for Supreme Court from everyone in Illinois will count the same. And while the new 3rd District leans more to the left than it used to, the race for Supreme Court is overall pretty competitive, and more likely to go to candidates from the party that wins the most votes for Supreme Court in the state overall.

It still seems likely that Democratic legislators wanted to draw a new map to give their vulnerable Illinois Supreme Court candidates a better chance of winning. However, existing rules made it difficult for them to draw an unfair map, so the best way they had of helping their candidates was to draw a map that was actually good for the state. Ideally, though, they would not get the chance.